William H. Kirkaldy-Willis, MD, had an accomplished professional career.

Dr. Kirkaldy-Willis was trained as an orthopedic surgeon. From 1965 to 1988 he was associated with the University Hospital in Saskatoon, Canada where he became Emeritus Professor of Orthopedic Surgery and Head of the Department in 1967.He was President of the East African Association of Surgeons (1959-1960); President of the Canadian Orthopedic Research Society (1971-1972); President of the International Society for Study of the Lumbar Spine (1982-1983); President of the North American Spine Society (1986-1987); and President of the American Back Society (1988-1991).

In his career, Dr. Kirkaldy-Willis published 71 articles that are indexed in the National Library of Medicine, and he was the primary author of the universally accepted gold standard reference text Managing Low Back Pain, which published four editions between 1983 and 1999.

Dr. Kirkaldy-Willis died in 2006 at the age of 93.

The August 15, 2006 issue of the journal Spine printed a tribute to Dr. Kirkaldy-Willis, which included these words (1):

Kirkaldy-Willis was one of the very few spine surgeons who recognized, at the very beginning, the important role of exercise in maintaining a healthy spine. An important special interest of his was in promoting cooperation between physicians and chiropractors to the benefit of both.

In 1985, Dr. Kirkaldy-Willis was the lead author of a study published in the journal Canadian Family Physician (2), titled:

“Spinal Manipulation in the Treatment of Low back Pain”

In this study, Dr. Kirkaldy-Willis notes that spinal manipulation is one of the oldest forms of therapy for back pain, and that it has mostly been practiced outside of the medical profession. He further notes that there has been an escalation of clinical and basic science research on manipulative therapy, which has shown that there is a scientific basis for the treatment of back pain by manipulation.

In this study, Dr. Kirkaldy-Willis discusses that a specific diagnosis and pathology is not evident in most cases of low back pain, but that compressive neuropathology is extremely rare. Specifically, he states:

“Most causes of low back pain lack objective clinical signs and overt pathological changes.”

“Less than 10% of low back pain is due to herniation of the intervertebral disc or entrapment of spinal nerves by degenerative disc disease.”

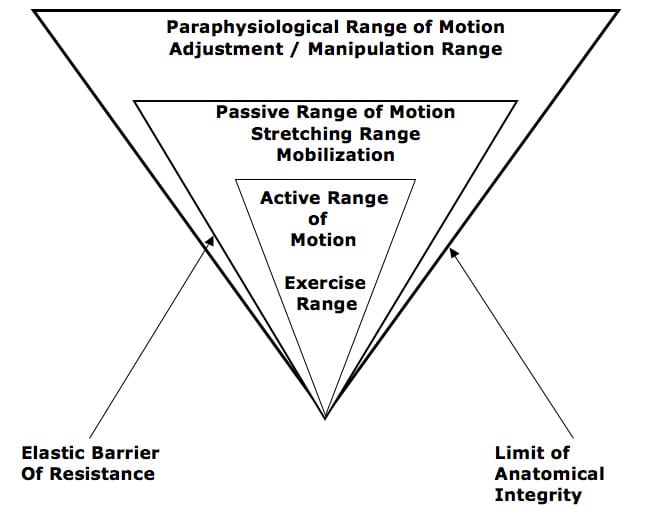

Dr. Kirkalady-Willis discusses how the key to successfully managing chronic low back pain is through the utilization of applied motion. He categorizes applied motion into three groups:

- Active Range of Motion

This range is achieved through active exercise. - Passive Range of Motion

Beyond the end of the Active Range of Motion of any synovial joint, there is a small passive range of mobility. A joint can only move into this zone with passive assistance. Going into this Passive Range of Motion constitutes mobilization. This is not manipulation. - Paraphysiological Range of Motion

At the end of the passive range of motion, an elastic barrier of resistance is encountered. This barrier has a “spring-like end-feel.” When motion separates the articular surfaces of a synovial joint beyond this elastic barrier, the joint surfaces suddenly move apart with a cracking noise. This additional motion can only be achieved after cracking the joint and has been labeled the Paraphysiological Range of Motion. This constitutes manipulation. Spinal manipulation is an assisted passive motion applied to the spinal facet joints that creates motion into the Paraphysiological Range.

The cracking sound on entering the Paraphysiological Range of Motion is the result of sudden liberation of synovial gases—a phenomenon known to physicists as cavitation.

At the end of the Paraphysiological Range of Motion, the limit of anatomical integrity is encountered. The facet joint capsular ligaments create the limit of anatomical integrity.

••••

In this study, Dr. Kirkaldy-Willis presents the results of a prospective observational study of spinal manipulation in 283 patients with chronic low back and leg pain. All 283 patients in this study had failed prior conservative and/or operative treatment, and they were all totally disabled (“Constant severe pain; disability unaffected by treatment.”)

These patients were given a two or three week regimen of daily spinal manipulations by an experienced chiropractor. No patients were made worse by the manipulation, yet many experienced an increase in pain during the first week of treatment. Even with this initial increase in pain, Dr. Kirkaldy-Willis emphasized the importance of continuing with manipulative treatment and not stopping treatment. He states:

“In most cases of chronic low back pain, there is an initial increase in symptoms after the first few manipulations. In almost all cases, however, this increase in pain is temporary and can be easily controlled by local application of ice.”

“Patients undergoing manipulative treatment must therefore be reassured that the initial discomfort is only temporary.”

In this study, Dr. Kirkaldy-Willis considered a good clinical outcome from manipulation to be:

- “Symptom-free with no restrictions for work or other activities.”

- “Mild intermittent pain with no restrictions for work or other activities.”

81% of the patients with referred pain syndromes subsequent to joint dysfunctions achieved the “good” result.

48% of the patients with nerve compression syndromes, primarily subsequent to disc lesions and/or central canal spinal stenosis, achieved the “good” result.

These results are impressive, especially considering that all of the patients were chronic, disabled and had failed prior conservative and surgical approaches to their problems.

••••

To explain the impressive outcomes from this study, Dr. Kirkaldy-Willis used the Gate Theory of Pain. Ronald Melzack and Patrick Wall first proposed the Gate Theory of Pain in 1965 (3). In discussing Melzack and Wall’s Gate Theory of Pain, Dr. Kirkaldy-Willis states that this theory has “withstood rigorous scientific scrutiny.” He specifically makes these additional observations:

“The central transmission of pain can be blocked by increased proprioceptive input.” Pain is facilitated by “lack of proprioceptive input.” This is why it is important for “early mobilization to control pain after musculoskeletal injury.”

The facet capsules are densely populated with mechanoreceptors. “Increased proprioceptive input in the form of spinal mobility tends to decrease the central transmission of pain from adjacent spinal structures by closing the gate. Any therapy which induces motion into articular structures will help inhibit pain transmission by this means.”

Importantly, Dr. Kirkaldy-Willis pioneered the concept of the “three joint complex.” This concept stresses that the function of the two facet joints are always linked to the function of the intervertebral disc. In other words, the facets and the disc are mechanically linked.

••••

As noted, Dr. Kirkaldy-Willis’ discussion of the Gate Theory of Pain involved the “closing” of the pain gate through the enhancement of proprioception. This was done by increasing the firing of mechanoreceptors of the facet joints, which occurred as a consequence of moving the facet joints into the Paraphysiological Range of Motion via spinal manipulation.

Many other authors make similar claims concerning the Gate Theory of Pain, including the following:

Remember:

Pain afferents are small diameter neurons.

Mechanoreceptors are large diameter neurons.

- The perception of pain is dependent upon the balance of activity in large [mechanoreceptor] and small [nociceptive] afferents. (4)

- If large myelinated fibers (mechanoreceptors) were selectively stimulated, then normal “balance” of activity between large [mechanoreceptor] and small [nociceptive] fibers would be restored and the pain would be relieved. (5)

- “Pain is not simply a direct product of the activity of nociceptive afferent fibers but is regulated by activity in other myelinated afferents that are not directly concerned with the transmission of nociceptive information.” (6)

- “The idea that pain results from the balance of activity in nociceptive and non-nociceptive afferents was formulated in the 1960s and was called the gate control theory.” (6)

- “Simply put, non-nociceptive afferents ‘close’ and nociceptive afferents ‘open’ a gate to the central transmission of noxious input.” (6)

- “The balance of activity in small- and large-diameter fibers is important in pain transmission...” (7)

In 2002, the British Journal of Anaesthesia published a study reaffirming the validity of the Gate Theory of Pain in an article titled (8):

“Gate Control Theory of Pain Stands the Test of Time”

••••

Proprioception is the sense of the relative position of neighboring parts of the body. Proprioception can be either conscious or unconscious, and both types aid in “closing” the pain gate. Proprioception includes both position sense and motion sense (kinesthesia).

It is proprioception that allows people to drive without having to look at one’s feet, to type without having to look at one’s fingers, and to run and catch a ball without having to look at one’s feet or hands.

Proprioceptive sense is composed of information from sensory neurons of the vestibular apparatus of the inner ear and from mechanoreceptors located in the muscles and joint tissues. Proprioception is awareness of position and/or movement derived from muscular, tendon, and articular sources. The awareness is derived from mechanoreceptive nerve endings that transmit data from joint capsules and muscles. Joint and muscle mechanoreceptors drive an important component of proprioception. Occasionally, joint mechanoreceptors are called “proprioceptors.”

In 1975, Princeton educated physiologist Irvin Korr, PhD, published a study titled (9):

Proprioceptors and Somatic Dysfunction

In this study, Dr. Korr notes that proprioceptors “from countless thousands of reporting stations and articular components, entering the cord via the dorsal roots, is essential to the moment-to-moment control and fine adjustment of posture and locomotion.”

Dr. Korr discusses the feedback loop that exists between these proprioceptors and the muscle system. He notes that adverse or inappropriate mechanical events can create a mismatch of communication within the feedback loop, which is deleterious [opens the pain gate]. He also notes how the adverse loop can be corrected through spinal manipulation.

••••

The Mechanoreceptors

Melzack and Wall’s Gate Theory of Pain was published in 1965. Dr. Korr’s article on proprioceptors was published in 1975. Dr. Kirkaldy-Willis’ article on manipulation and the Gate Theory of Pain was published in 1985. Since 1985, a number of studies have investigated the anatomy and physiology of joint mechanoreceptors, often using human subjects. Several of these are listed below:

In 1992, the journal Spine published a study titled (10):

“Neural Elements in Human Cervical Intervertebral Discs”

The authors document that the human cervical intervertebral disc is innervated with mechanoreceptors. They state:

“The presence of neural elements within the intervertebral disc indicates that the mechanical status of the disc is monitored by the central nervous system.”

“The location of the mechanoreceptors may enable the intervertebral disc to sense peripheral compression or deformation as well as alignment.”

Key points from this study include:

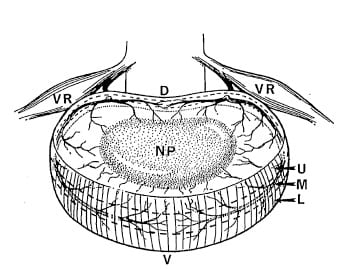

- The intervertebral disc is innervated with mechanoreceptors, perhaps as deep as to the nucleus pulposus.

- These mechanoreceptors communicate to the central nervous system.

- These mechanoreceptors provide basic proprioceptive function, specifically the sense of compression, deformation, and alignment.

••••

In 1994, the journal Spine published a study titled (11):

“Mechanoreceptor endings in human cervical facet joints”

These authors state:

“Encapsulated mechanoreceptors are a consistent finding in normal human cervical facets.”

“The presence of these receptors in the facet capsule indicate that the mechanical state of the capsule (position, tension, pressure, etc.) is under the surveillance of the central nervous system.”

“The presence of mechanoreceptive and nociceptive nerve endings in cervical facet capsules proves that these tissues are monitored by the central nervous system and implies that neural input from the facets is important to proprioception and pain sensation in the cervical spine.”

Key points from this study include:

- The cervical facet joints are innervated with mechanoreceptors.

- These mechanoreceptors communicate to the central nervous system.

- These mechanoreceptors provide basic proprioceptive function, specifically the sense of tension, pressure, and position.

••••

In 1998, the same primary author and colleague investigated the presence of mechanoreceptors in the facets joints of the thoracic and lumbar spines. They published their findings in Spine in an article titled (12):

“Mechanoreceptor endings in human thoracic and lumbar facet joints”

These authors state:

“Ongoing studies of spinal innervation have shown that human facet tissues contain mechanoreceptive endings capable of detecting motion and tissue distortion.”

“Encapsulated nerve endings are believed to be primarily mechanosensitive and may provide proprioceptive and protective information to the central nervous system regarding joint function and position.”

Key points from this study include:

- The thoracic and lumbar facet joints are innervated with mechanoreceptors.

- These mechanoreceptors communicate to the central nervous system.

- These mechanoreceptors provide basic proprioceptive function, specifically the sense of motion, tissue distortion, and position.

••••

In 1995, the journal Spine published a study titled (13):

“Mechanoreceptors in intervertebral discs:

Morphology, distribution, and neuropeptides”

The authors documented the occurrence and morphology of mechanoreceptors in human and bovine intervertebral discs and longitudinal ligaments. They note that:

Physiologically, these mechanoreceptors “provide the individual with sensation of posture and movement.”

“In addition to providing proprioception, mechanoreceptors are thought to have roles in maintaining muscle tone and reflexes.”

“Their presence in the intervertebral disc and longitudinal ligament can have physiologic and clinical implications.”

Key points from this study include:

- The lumbar intervertebral discs are innervated with mechanoreceptors.

- These mechanoreceptors provide basic proprioceptive function, including the maintenance of muscle tone and muscular reflexes.

••••

More recently, in 2010, the Journal of Clinical Neuroscience published a study titled (14):

“An immunohistochemical study of mechanoreceptors in lumbar spine intervertebral discs”

The study used twenty-five lumbar (L4–5 and L5–S1) fresh human intervertebral discs. These authors state:

“These receptors have a key role in the perception of joint position and adjustment of the muscle tone of the vertebral column.”

“An important component of low back pain is an intense muscle spasm of the vertebral musculature, elicited through reflex arches mediated by specialized nerve endings.”

“During axial loading of a motion segment, compressive stresses in the nucleus will generate tensile stresses in the peripheral annulus, which is rich in neural receptors.”

“In conclusion, this study confirms the existence of an abundant network of encapsulated and non-encapsulated receptors in the intervertebral discs of the lower lumbar spine in normal human subjects. The principal role of encapsulated structures is assumed to be the continuous monitoring of position, velocity and acceleration (kinesthesia).”

Key points from this study include:

- The lumbar intervertebral disc is innervated with mechanoreceptors.

- These mechanoreceptors are important in maintaining proper muscle tone and when dysfunctional can create intense muscle spasms.

- These mechanoreceptors provide basic proprioceptive function, specifically the sense of compression, deformation, kinesthesia, and alignment.

••••

SUMMARY

Spine pain is extremely common in our society. Chemical (pharmaceutical) approaches to the management of spinal pain syndromes are also common and popular. Chemical (pharmaceutical) approaches for pain management are marketed on television, radio, internet, and printed media, etc. These chemical (pharmaceutical) products are both over the counter and prescription.

When a patient presents with spinal pain syndrome to a chiropractic office, history usually reveals that a chemical (pharmaceutical) solution has been tried or is concurrently being tried, often with unacceptable results. In these cases, chiropractors primarily look for mechanical problems.

The basic premise, as supported above, is that physical stresses and/or trauma result in mechanical problems. These mechanical problems impair the appropriate function of articular mechanoreceptors. These articular mechanoreceptors are proven to exist, as noted above. These articular mechanoreceptors have three primary functions:

- Control, through neurological reflexes, the tone in the related musculature. This enhances spinal function and protects the spinal joints against additional injury and future degenerative processes.

- Provide proprioceptive senses to the central nervous system. This includes information on alignment, position, compression, deformation, and motion. Once again, this enhances spinal function and protects the spinal joints against additional injury and future degenerative processes.

- The quality of the mechanoreceptive input and proprioception are a significant factor in the state of the Pain Gate. Simply put, improved mechanoreception and proprioception close the Pain Gate.

According to low back pain pioneer, Dr. Kirkaldy-Willis, spinal adjusting (manipulation) influences and benefits the back pain patient through two mechanisms:

- Stretching of facet joint capsules will fire capsular mechanoreceptors which will reflexly “inhibit facilitated motoneuron pools” which are responsible for the muscle spasms that commonly accompany low back pain. Not only does spasm relief improve a patient’s pain, it also improves spinal motion, improves spinal mechanoreception, improves proprioception, and further inhibits pain by closing the Pain Gate.

- In chronic cases, there is a shortening of periarticular connective tissues and intra-articular adhesions may form. Orthopedically trained chiropractors refer to these soft tissue changes as the “Fibrosis of Repair.” Dr. Kirkaldy-Willis suggests that spinal adjusting (specific line-of-drive manipulation) will stretch or break these adhesions, and enhance remodeling of other fibrotic tissue changes. These also give the patient long-term improvement in joint function, mechanoreception, proprioception, neuromuscular controls and Pain Gate closure.

Importantly, Dr. Kirkaldy-Willis notes that once an adjustment breaks the adhesion, they will often reform to create the same degree of adverse joint mechanical function. His solution, as documented in his 1985 study above (2), is that the patient be adjusted daily for two to three weeks, at a minimum. His study included prior chiropractic failures, and he attributed the success of the new chiropractic intervention to daily spinal adjusting for two to three weeks. Dr. Kirkalady-Willis states:

“However, the gain in mobility must be maintained during this period to prevent further adhesion formation.”

“In our experience, anything less than two weeks of daily manipulation is inadequate for chronic low back pain patients.”

It is chiropractically important to understand that the intervertebral disc and facet capsules (and other tissues) are innervated with mechanically sensitive nerves that communicate with the central nervous system. These nerves tell the CNS about the mechanical status of spinal function and alignment of the spine, as well as controlling local neuromuscular reflexes and the Pain Gate. Undoubtedly, chiropractic adjustments influence these nerves both during an adjustment and afterwards as a consequence of improved biomechanical function and posture.

REFERENCES:

- In Memoriam, A Tribute to William Kirkaldy-Willis; Spine; Vol. 31; No. 18; Aug. 15, 2006; pp. 2034-2035.

- Kirkaldy-Willis WH and Cassidy JD; Spinal Manipulation in the Treatment of Low back Pain; Canadian Family Physician; March 1985, Vol. 31, pp. 535-540.

- Melzack R, Wall P; Pain mechanisms: a new theory; Science; November 19, 1965;150(3699); pp. 971-979.

- John Nolte, The Human Brain, Mosby Year Book, 1993, p. 139.

- John Nolte, The Human Brain, Mosby Year Book, 1999, p. 203.

- Eric Kandel, James Schwartz, Thomas Jessell, Principles of Neural Science. McGraw-Hill, 2000, pp. 482-3.

- Eric Kandel, James Schwartz, Thomas Jessell, Principles of Neural Science, McGraw-Hill, 2000, pp. 490.

- Dickenson AH; Gate Control Theory of Pain Stands the Test of Time; British Journal of Anaesthesia; June 2002; Vol. 88; No. 6; pp. 755-757.

- Korr IM; Proprioceptors and somatic dysfunction; Journal of the American Osteopathic Association; March 1975; Vol. 74; No. 6; pp. 683-650.

- Mendel T, Wink CS, Zimny ML; Neural elements in human cervical intervertebral discs; Spine; February 1992;17(2):pp. 132-5.

- McLain RF; Mechanoreceptor endings in human cervical facet joints; Spine; March 1, 1994;19(5):495-501.

- McLain RE, Pickar JG; Mechanoreceptor endings in human thoracic and lumbar facet joints; Spine; January 15, 1998;23(2):168-73.

- Roberts S, Eisenstein SM, Menage J, Evans EH, Ashton IK; Mechanoreceptors in intervertebral discs: Morphology, distribution, and neuropeptides; Spine; December 15, 1995;20(24): pp. 2645-51.

- Dimitroulias A, Tsonidis C, Natsis K, Venizelos I, Djau SN. Tsitsopoulos P; An immunohistochemical study of mechanoreceptors in lumbar spine intervertebral discs; Journal of Clinical Neuroscience; Volume 17, Issue 6, June 2010, Pages 742-745.